By Deborah Kops

It starts innocently enough. A global process owner proves to be an exceptional transformation champion. A center leader shows unexpected aptitude for business relationship management. A respected functional delivery lead suddenly finds themselves “voluntold” to take on pan-GBS capabilities like service management or automation. Before you know it, they’ve become a double-hatter.

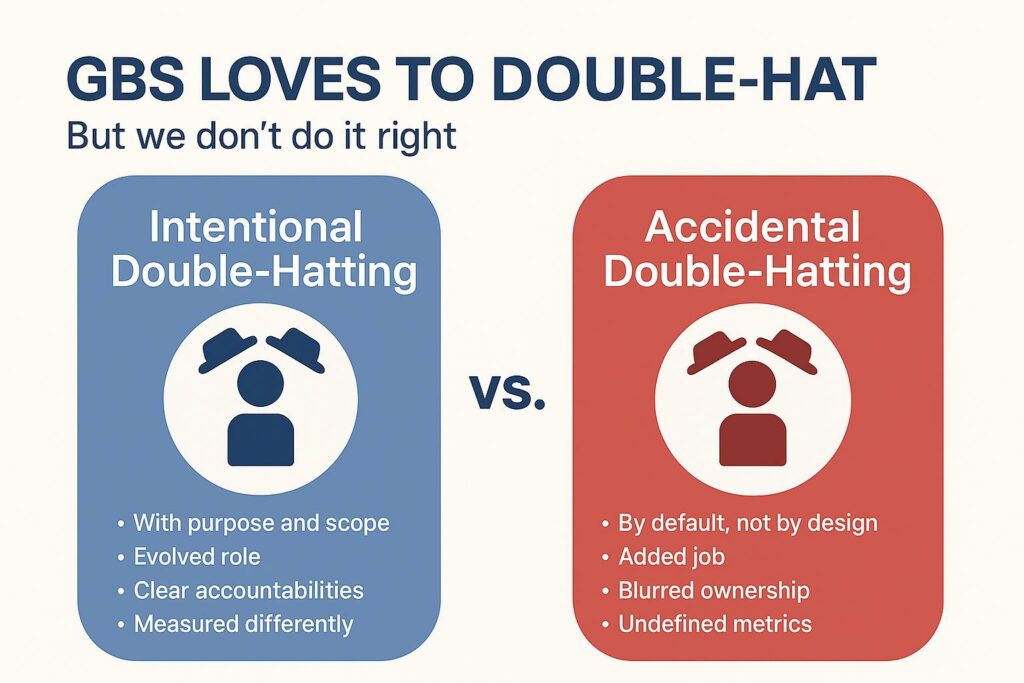

Double-hatting—the practice of assigning a leader two roles within a global business services organization—is increasingly touted as a pragmatic solution in fast-evolving organizations. And in the right context, it can be a great catalyst for alignment, integration, and talent development.

But let’s not kid ourselves. When misapplied, double-hatting can create confusion, stall momentum, and expose the GBS model to credibility and execution risk.

So let’s unpack it. When does double-hatting work? When does it backfire? And how can GBS leaders use it as an effective tool without turning it into a crutch?

The case for double-hatting

In an era where winners are flexible and agile, double-hatting is a great way not only to open up new career possibilities for talent, but also to move the dial on GBS performance. Here’s why:

1. Accelerates alignment across GBS roles and capabilities.

Most GBS organizations find themselves siloed. We segregate talent into process towers. Isolate regional delivery. Align enabling capabilities and relationship management to functions.

Double-hatting can bridge those seams. A center lead who also serves as a BRM, for example, brings operational insight directly into business conversations. A transformation lead who also owns process excellence ensures change isn’t disconnected from delivery.

2. Creates real accountability.

One of the persistent GBS risks is a lack of ownership across horizontal activities. A double-hatted leader can’t pass the buck—they are the buck. When your transformation leader also owns change, or your regional head doubles as the I2P process owner, the model can drive outcomes, not excuses.

3. Grows integrator talent.

Too often, GBS career paths reinforce silos—delivery vs. design, operations vs. customer experience. Double-hatting gives high performers a way to develop range: to influence and execute, to zoom in and zoom out. That’s how you build future GBS leaders.

4. Buys time while the model matures and the budget expands.

Let’s be real. GBS organizations are usually resource-constrained, evolving, and under pressure to deliver yesterday. Double-hatting a capable leader can stabilize operations or jumpstart transformation while the long-term org structure catches up.

But here’s the catch…

1. It’s usually not a part-time gig.

Each GBS role—global process owner, center lead, BRM, transformation exec—comes with a full slate of expectations. Slapping a second remit on someone without resetting scope, deliverables, and support is a fast track to burnout and disengagement.

2. Role clarity goes foggy fast.

Double-hatting only works when everyone, especially the leader, knows which hat is on in which moment. Are they in the room as a process owner or as the regional lead? Are they solving for delivery or designing for the future? Ambiguity slows decision-making and undermines credibility.

3. It can dilute influence.

In GBS, influence is currency. But when a leader is spread too thin, their presence—and their power—diminish. They risk becoming reactive, focused on operational firefighting rather than shaping the model.

4. It may stall team motivation.

If one person is holding multiple remits, what does that mean for the next layer of talent? When direct reports see the same people occupying all the deck chairs with no opportunity to step up, motivation and retention take a hit.

How does GBS master double-hatting?

1. Be explicit about its purpose.

Double-hatting should never be the default organizational construct. It should be deployed with intent—whether to test a model, develop a successor, or bridge a temporary capability gap. And always define a time horizon.

2. Redesign the role, don’t just pile on a second shift.

This is key. Don’t treat the second hat as an “add-on.” Reframe the combined responsibilities as one reimagined role with clearly articulated outcomes, new success metrics, and adjusted scope.

3. Support with actual infrastructure.

Give your double-hatted leaders deputies, analyst support, or dedicated program managers. If they’re going to take accountability to deliver on multiple remits, they need bandwidth to think, lead, and execute.

4. Celebrate the role publicly.

Use double-hatting to make it clear that the organization values integration, not just output. Acknowledge the challenge and complexity, visibly reward the performance, and use the role to role-model what next-gen GBS leadership looks like.

5. Review and evolve.

Double-hatting should be dynamic. Hats should be changed regularly to adapt to business needs. Is the structure still serving the mission? Has the leader outgrown the role? Is it time to split the hats and create new opportunities for the bench?

The last word

Double-hatting inside GBS isn’t a workaround—it should be a deliberate organizational choice. One that, when executed well, unlocks agility, capability, and leadership growth. But like any structural choice, it carries risk if applied too broadly, too long, or without adequate resourcing.

Used wisely, double-hatting can elevate GBS from siloed service lines to a truly integrated operating model. Misused, it becomes a drag on momentum and a barrier to scale.

The trick is knowing the difference—and having the discipline to act on it.

What starts as a clever way to bridge silos or buy time can quickly turn into a structural bad habit—one that blurs accountability, burns out talent, and tests the limits of every GBS leader.